On Not Being a Scoundrel

A question and a speech that helps students’ ability to make sense of ethical lapses and failures in the law.

NOTE: This essay is the first in an occasional series of Leadership and Character Ideas, where Program faculty, staff, and affiliates present essays on how leadership and character can be taught and applied to our modern lives.

I teach courses in leadership and ethics in the law, and I begin most of those courses by asking students a series of questions, including: “By a show of hands, how many of you think there’s a decent chance you’ll go to prison for something you do related to your future work as a lawyer?”

That question frequently garners chuckles. I am pleased to report that no student has yet to raise a hand.

You may think that highlighting the threat of prison as a motivation for virtue development is a bit much. Don’t we want students who are intrinsically motivated to pursue all that is right, good, and true and not simply to threaten our students into conformity?

Yes. Of course. I have found that some students are more intrinsically motivated than others. All are concerned, however, about not going to prison or being disbarred from the profession. This common concern helps to focus their attention.

The question is one way for my students and me to start making sense of all of the ethical lapses and failures in the law. What, if anything, separates my students from the approximately 4-5% of American lawyers who will be disciplined at some point in their careers? What can I do with my students now to minimize the chances that they end up doing something, or becoming someone, they cannot at present imagine possible? And how can I help them avoid making moral mistakes that may never be punished but nonetheless impede their flourishing and the flourishing of their clients and communities?

Later in the semester, as we study lawyers-gone-bad, we revisit these questions. I then introduce them to “The Inner Ring,” a speech from C.S. Lewis that he delivered to a group of graduating students in London in 1944, many of whom may be seduced by similar but subtle temptations to abandon their character. Here’s an excerpt:

[T]he prophecy I make is this. To nine out of ten of you the choice which could lead to scoundrelism will come, when it does come, in no very dramatic colours. Obviously bad men, obviously threatening or bribing, will almost certainly not appear. Over a drink, or a cup of coffee, disguised as triviality and sandwiched between two jokes, from the lips of a man, or woman, whom you have recently been getting to know rather better and whom you hope to know better still—just at the moment when you are most anxious not to appear crude, or naïf or a prig—the hint will come. It will be the hint of something which the public, the ignorant, romantic public, would never understand: something which even the outsiders in your own profession are apt to make a fuss about: but something, says your new friend, which “we”—and at the word “we” you try not to blush for mere pleasure—something “we always do.”

And you will be drawn in, if you are drawn in, not by desire for gain or ease, but simply because at that moment, when the cup was so near your lips, you cannot bear to be thrust back again into the cold outer world. It would be so terrible to see the other man’s face—that genial, confidential, delightfully sophisticated face—turn suddenly cold and contemptuous, to know that you had been tried for the Inner Ring and rejected. And then, if you are drawn in, next week it will be something a little further from the rules, and next year something further still, but all in the jolliest, friendliest spirit. It may end in a crash, a scandal, and penal servitude; it may end in millions, a peerage and giving the prizes at your old school. But you will be a scoundrel.

In this telling, “scoundrelism” has a way of sneaking up on us. But what I attempt to impart to my students is that they—and we—are not helpless in the face of such forces. By engaging exemplars, establishing good habits, and practicing self-reflection, we can become better attuned to the threats of scoundrelism, and we can cultivate the courage, wisdom, and integrity that helps us resist these threats. We can resist extraordinary vice with ordinary virtue.

This attention to virtue, of course, has broader implications for professional education. If we merely focus on imparting knowledge and developing skills and ignore considerations of character or questions related to the public good, we will not be preparing our students to become the sort of professionals who recognize threats of scoundrelism or who are equipped to respond to those threats when they emerge.

Our work, in sum, is to educate, and to form, students to become successful professionals and flourishing human beings. This requires more than simple knowledge of right and wrong and the memorization of professional codes of conduct. Educating character goes beyond the checking of boxes. Holistic professional identity formation requires transmitting knowledge, cultivating skills, and developing character. It demands that we start with humility, with an approach which focuses on the needs of others.

Taking character seriously is not only an intrinsically worthwhile project, but it also happens to have very practical implications and benefits for professions, and professionals, under scrutiny. Character implicates identity and enables the professionals to connect who they are with what they do. As such, a character-based approach to professional formation holds the promise of enabling professionals to live more purposeful, integrated lives while also advancing social trust by improving the public’s perception that professionals are worthy of the trust they seek.

Character should not be undertaken solely as a way to avoid the worst outcomes, like disbarment, sanction, or even prison. It’s not a guide for how not to become a scoundrel. Instead, it’s a way for all of us, individually and together, to work toward becoming the professionals and people that we want to be.

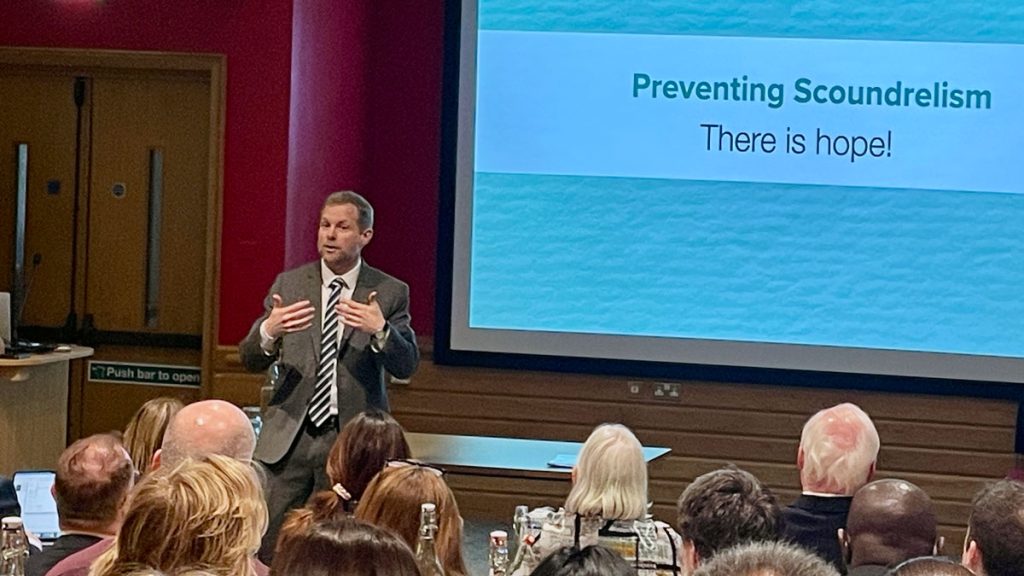

This essay was adapted from Townsend’s keynote address at the Jubilee Centre’s annual conference in January 2026. Other Program staff members who presented at the three-day event in Oxford were Eranda Jayawickreme, Michael Lamb, Becky Park, and Jennifer Rothschild.